If you are on the same side of the internet that I am, you would have seen a lot of discourse about “taste” as the key distinction between AI slop and great work.

That in a world where ChatGPT knows everything and the internet gives everyone access to the same archive, taste is what sets you apart.

Let’s get nuanced people.

I agree: in a world where AI can replicate knowledge and everyone scrolls the same feeds, taste does set you apart. But the way taste is being packaged - polished and made for virality - feels like it’s diluting the very thing it’s trying to defend. Taste isn’t just a buzzword or a branding tactic. It deserves more complexity than what the current conversation allows.

What has happed to taste in the modern age?

Taste is a peculiar concept. Clearly, we are all interested in it and we all want to know more because the algorithm is pushing it like crazy.

But when everyone starts talking about taste, especially in the same aesthetic tone and on the same platforms, it stops functioning as a mark of discernment and starts reinforcing homogenisation.

Algorithms have made taste predictable and repetitive. It’s something you can buy (by clicking on a ShopMy link…).

Social platforms are engineered around engagement metrics - likes, shares, saves. These metrics reward immediacy and virality, not depth. As a result:

Low-context, easy to understand content wins because it doesn’t require prior knowledge or emotional investment.

Aesthetic coherence becomes proxy for taste because it’s fast to grasp and easy to replicate.

Algorithmic incentives lead to convergence - everyone starts posting variations of the same “taste,” whether it’s quiet luxury or tomato girl summer.

Once taste is performative, a few things happen:

People curate identities - Taste is wielded as a tool to align with trends such that if you are carrying The Row 90’s Bag, you’re automatically deemed to have good taste

We start optimising for validation, not resonance. Instead of: Does this reflect me?, the internal filter becomes: Will people think I’m cool?

The platform shapes not just how we express taste, but what taste is allowed to be.

So, even if your taste is thoughtful, the platform pressures you to flatten it into something digestible - a moodboard, links, a top 10 list. It reduces something inherently nuanced into simplistic aesthetics that anyone can copy or paste.

Over time, this incentivises not cultivating and sharing your taste, but performance instead. What we post is less about what moves us and more about what aligns with the current taste discourse.

We’ve built systems that reward copying over originality, and we’re all performing our way further from ourselves.

Step into any “design-forward” space these days and you’ll see the same formula: an Eames lounge chair, a sculptural side table stacked with fashion or art tomes. A cool lamp perched on top, a potted plant to add some greenery.

Or this all-beige aesthetic we see so often in the kitchen.

It’s not that these spaces lack intention - it’s that we all know exactly which Pinterest board they came from. Taste has become so coded that it no longer signals discernment; it signals fluency in trends.

So if taste can’t be bought or copied, how do you actually build it?

Building taste

True taste is stubbornly individualistic. It emerges quietly, gradually, often through personal choices that might seem puzzling or eccentric to others but make perfect sense internally.

It lived in Lee Radziwill’s interiors - unstyled, uncrowded, impossible to pin down. In Diana Vreeland’s surreal Harper’s Bazaar column, where she famously asked, “Why don’t you… rinse your blond child’s hair in dead champagne to keep it gold, as they do in France?”

You didn’t need to agree. But you understood: this was a woman with a point of view.

Taste isn’t sexy to build. It’s slow, frustrating, and sometimes embarrassing. There’s a gap between your taste and your ability - and it’s uncomfortable to live in that space.

Paul Graham compares it to writing or painting - disciplines where the more you create, the more you refine your ability to spot what’s strong and what’s not. You make judgment calls. You train your instincts. You mess up and recalibrate. And over time, you internalise a mental model for quality that others can’t always articulate - but they can feel.

Intolerance for ugliness is not in itself enough. You have to understand a field well before you develop a good nose for what needs fixing. You have to do your homework. But as you become expert in a field, you'll start to hear little voices saying, What a hack! There must be a better way. Don't ignore those voices. Cultivate them. The recipe for great work is: very exacting taste, plus the ability to gratify it. - Paul Graham

Picasso lived for a total of 33,403 days. With 26,075 published works that means Picasso averaged 1 new piece of artwork every day of his life from age 20 until his death at 91. He created something new, every day, for 71 years.

Mozart lived for 35 years. In that time, he composed over 800 works - from operas to symphonies to sacred choral music.

As artists gain experience and refine their taste, they often begin to experiment more boldly with form and abstraction. Their taste and discernment is a byproduct of long, obsessive practice.

You can see this literally in Picasso’s self portraits over time:

The initial discomfort we experience when engaging with unfamiliar or unexpected ideas, artworks, or objects is precisely the friction that sharpens our sense of taste. Over time, these uncomfortable encounters enrich our perspectives, deepening our capacity for appreciation and nuance.

Is taste meant to be democratic?

If taste truly were the new universal intelligence, why do so many feel alienated from “good taste”?

I don’t think it’s because taste is inherently elitist. I think it’s because genuine taste takes work.

To appreciate, discern, and judge with authority, you need more than surface-level familiarity. Consider fashion, art, literature, or film; the more deeply you understand the complexities, historical contexts, and subtle nuances within these, the better understanding you have.

It’s like spotting a vintage Prada skirt at a thrift store: to most people, it’s just another black pencil skirt. But if you know what to look for, if you’ve studied the silhouettes and memorised the collections, you recognise it instantly for what it is.

True taste is inherently exclusive because it rests upon a foundation of informed insight rather than casual engagement.

Basically, we gotta stop being lazy people!

One of the books I studied during high school was The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot. I remember picking it up, skimming through and thinking it was an impossible task to analyse.

And honestly, without context, it kind of is. The poem is dense, layered with references to Greek mythology, Shakespeare, Eastern philosophy, post-war despair. Eliot expects you to put in the work to understand and learn his language.

The epigraph alone alludes to the type of book you are about to read: Four different languages in a few short lines: Latin, Greek, English, and Italian. Two different alphabets: Greek and Latin. In English:

Indeed, with my own eyes, I saw the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in a jar, and when the kids told her ‘Sibyl, what do you want?’, she answered, ‘I want to die.’

This quote references the Cumaean Sibyl, a prophetess in Greek and Roman mythology. She was granted eternal life by the god Apollo but forgot to ask for eternal youth. As a result, she withered away physically but could never die.

Taste, in this sense, is less about gut feeling, and more about possessing the intellectual tools to decode complexity. Every reference you unpack and understand is like a reward.

Taste isn’t elitist or exclusionary for the sake of exclusivity; rather, it recognises and values the depth of understanding required to meaningfully discern quality from mediocrity. Because real taste isn’t just a matter of preference - it’s a reflection of attention, study, and time.

Taste won’t save you on its own.

There’s a growing narrative that taste is the new superpower - the trait that separates originality from trend. But treating taste as a universal edge flattens the complexity of what actually drives success: timing, good products, execution, capital, and momentum.

Plenty of iconic brands weren’t built on great taste. Facebook didn’t win on aesthetics. Crocs didn’t need cool. They scaled by creating good products, meeting distribution and demand.

If Apple’s iPhone wasn’t a great product, it would have been a massive failure - no matter how hard Steve Jobs tried with great design.

Taste is a refinement layer. A beautiful idea with no execution is just a Pinterest board.

Ok - what can we do about it?

Ultimately, true taste isn’t about gatekeeping - it’s about respecting the time, effort, and depth it takes to develop real discernment.

How do you develop your own taste in a world that only shows you more of what you already like?

I like to look at a wide variety of things that make me feel happy or a certain way. For me, it’s very intuitive.

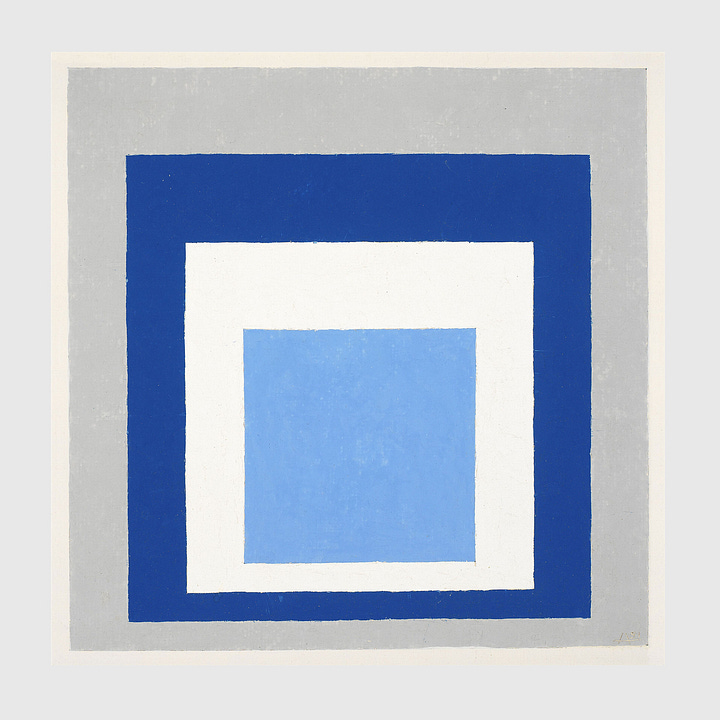

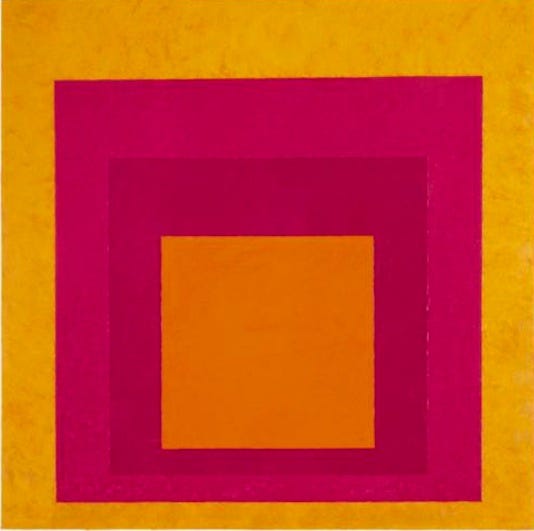

For example, I find a lot of inspiration in Josef Albers and his paintings:

In fact, we used his colours as inspiration for Rolodex’s branding. I think about his combinations when I am getting dressed quite often.

I also look to style icons like the Onassis sisters (for example I love the excessively large sunglasses paired with the headscarf that Jackie Kennedy often sported - definitely recreating this).

If you know me, my ultimate style icon for years has been CBK. And no, I don’t want to talk about the Ryan Murphy remake. I have no words. Those converses should be burned.

Final words

In the end, the real threat to taste isn’t AI - it’s the way content keeps trying to package it. The more we polish it for virality, the more we strip it of what made it powerful in the first place.

Developing taste means actively resisting the gravitational pull of popular consensus and algorithmic predictability. It means allowing yourself to be guided by intuition and curiosity rather than the expectation of external validation. It means being conscious and careful about the clothes you buy, the books you read, the music you listen to. Above all, it means learning.

Taste doesn’t just come from liking things.

It comes from disliking things - and knowing why.

Your writing style alone has convinced me to subscribe

Everything is now beige and grey and uniform and ugly... And that's the problem